By: Abigail Zeller

In January 2016, the National Football League (NFL) agreed to allow the St. Louis Ram’s to relocate to Los Angeles (LA). As part of that agreement, the NFL also gave the San Diego Chargers a one-year option to join the Rams in LA. Recently, the Chargers exercised that option and reached an agreement that will allow them to play in the new Inglewood Stadium, which is which is slated for completion in 2019.

Even though the Chargers move was announced only a few weeks ago, the team took steps to protect its intellectual property interests much earlier. For example, almost a year ago the Chargers Football Company (owner of the team) filed trademark applications with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) for the marks, “LA CHARGERS” and “LOS ANGELES CHARGERS” for products such as toys, apparel, and, of course, for “professional football games and exhibitions.”

Unfortunately for the Chargers, LA GEAR, a well-known athletic apparel company, recently filed a Notice of Opposition against the “LA CHARGERS” trademark application. A Notice of Opposition is legal challenge to the right to register a particular trademark. Most often, a trademark application is opposed by someone who owns prior rights in an identical or confusingly similar trademark.

In this instance, LA GEAR’s opposition asserts that the “LA CHARGERS” trademark conflicts with its own trademarks, and is likely to cause consumer confusion, leading consumers to incorrectly believe that the “LA CHARGERS” goods originate from LA GEAR. This argument, known as “likelihood of confusion,” is the core claim of a trademark infringement suit. Trademark law protects trademark owners from others who use marks that are identical or, as LA GEAR alleges, confusingly similar to the trademark owner’s marks.

If the USPTO rules in LA GEAR’s favor, the Charger’s may be forced to take corrective action, e.g., by rebranding the team with a new mark that is not confusingly similar to LA GEARS’ marks. Alternatively, the Chargers could challenge the decision in federal court or attempt to settle the matter with LA GEAR privately.

In addition to LA Gear’s opposition, the Chargers’ new logo faced widespread criticism on the basis that it was too similar to the logo of other major sports teams, most notably the LA Dodgers (see below). In the face of such criticism, the Chargers revised their new logo several times before finally settling on a variation resembling the Chargers’ original logo.

The circumstances facing the Chargers emphasize the importance of performing trademark due diligence when branding any company, no matter how big or small. Among other things, trademark due diligence includes searching existing trademark records to determine the availability and overall protectibility of a chosen trademark, as well as the risk of potential conflicts down the line. Although U.S. law does not require that trademark searches be conducted prior to using and/or filing an application to register a trademark, conducting such a search can help uncover risks and save time and headaches down the road.

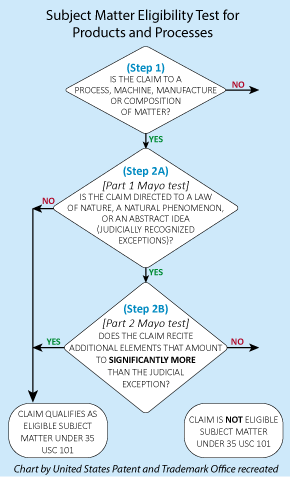

Prompting a collective sigh of relief from patent attorneys that represent clients in the software industry, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Enfish LLC v. Microsoft reversed a lower court’s holding that Enfish’s patent claims – which are directed to software – were invalid for claiming patent-ineligible subject matter under 35 US Code Section 101.

Prompting a collective sigh of relief from patent attorneys that represent clients in the software industry, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Enfish LLC v. Microsoft reversed a lower court’s holding that Enfish’s patent claims – which are directed to software – were invalid for claiming patent-ineligible subject matter under 35 US Code Section 101.